1

Summary

Healthcare occupations account for a large and growing share of the workforce and span the education and earnings continuum. Although many discussions of the healthcare workforce focus on doctors and other occupations requiring advanced degrees, the healthcare system would not function without pre-baccalaureate workers—those with less than a bachelor’s degree. These workers perform a variety of clinical, assistive, and administrative tasks, and like all healthcare staff, should be working at their full level of competence in order to achieve the “triple aim” of improving the experience of care, improving health outcomes, and reducing per capita costs.

While individuals with less than a bachelor’s degree work in multiple healthcare occupations, they are overwhelmingly concentrated in a subset of occupations. This report identifies the 10 largest “pre-baccalaureate” healthcare occupations, those in which substantial shares of workers—ranging from 39 percent to 94 percent—have less than a bachelor’s degree, and focuses on those workers in the 10 occupations, unless otherwise noted. Using labor market and American Community Survey data from 2000 and 2009-2011, our analysis across the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas finds that:

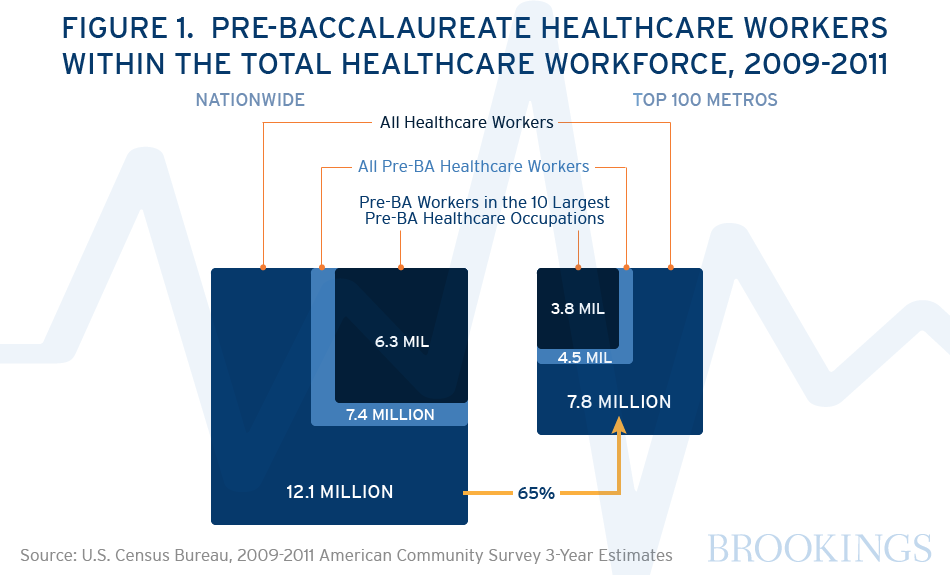

- Workers with less than a bachelor’s degree in the 10 largest pre-baccalaureate healthcare occupations total 3.8 million, accounting for nearly half (49 percent) of the total healthcare workforce in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas. Occupations with the highest numbers of pre-baccalaureate workers include nursing, psychiatric and home health aides (1.2 million), registered nurses (680,000), personal care aides (542,000), and licensed practical nurses (343,000).

- Educational attainment varies considerably among workers in pre-baccalaureate healthcare occupations, and earnings largely track education.Pre-baccalaureate RNs and diagnostic technologists and technicians typically have associate’s degrees or other post-secondary educational experience and have the highest median annual earnings (full-time, year-round) of pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers, at $60,000 and $52,000 respectively. By contrast, about half of personal care aides and nursing, psychiatric and home health aides have a high school diploma or less, and post median annual earnings of $21,000 and $25,000, respectively.

- · Pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers in the 10 largest pre-baccalaureate healthcare occupations are racially and ethnically diverse and overwhelmingly female. Men are a minority in all of the occupations except for emergency medical technicians / paramedics. Half of the occupations have higher shares of blacks, Asians and Hispanics than the average among pre-baccalaureate workers across all occupations. Moreover, the pre-baccalaureate healthcare workforce has grown more diverse over time: in 2009-11, whites made up 49 percent of pre-baccalaureate workers in the 10 highlighted occupations, down from 59 percent in 2000. Foreign-born workers are especially concentrated among pre-baccalaureate personal care aides and nursing, psychiatric and home health aides.

- The number of jobs held by pre-baccalaureate workers in the 10 largest pre-baccalaureate healthcare occupations increased at a faster rate than jobs held by similarly educated workers overall, but the largest growth was among lower-paying pre-baccalaureate healthcare occupations, and only registered nurses experienced real earnings growth between 2000 and 2009-11. The number of jobs held by pre-baccalaureate workers in the 10 highlighted occupations increased by 46 percent between 2000 and 2009-11, compared to growth of 3 percent among pre- baccalaureate workers across all occupations. The bulk of the growth was among occupations with lower earnings, particularly personal care aides, whose numbers rose by nearly 400,000 (278 percent). Pre-baccalaureate RNs were the only occupation to post statistically significant real earnings growth between 2000 and 2009-11, with a 6 percent increase in annual median earnings ($3,300). By contrast, median earnings among pre-baccalaureate workers across all industries and occupations fell by 14 percent, or about $5,500.

- The size and nature of the pre-baccalaureate healthcare workforce varies by region, reflecting demographics and healthcare industry mix. Pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers in the 10 highlighted occupations account for lower shares of the total healthcare workforce in more highly-educated regions that are often home to medical schools and teaching hospitals, and higher shares of the healthcare workforce in areas with smaller numbers of such institutions, and with lower levels of education and older populations. Pre-baccalaureate workers in the 10 highlighted occupations range from 37 percent and 40 percent of all healthcare workers in the Denver, CO and San Jose, CA metropolitan areas, respectively, to 63 percent and 72 percent of all healthcare workers in the Modesto, CA and McAllen, TX metropolitan areas, respectively.

It is a dynamic moment for the healthcare industry, which is experiencing multiple pressures for change: expanded access, an aging population, technological advancements, cost-reduction imperatives, and most importantly, a call for improved health outcomes. Healthcare providers and insurers are experimenting with new or adapted models to finance and deliver care, with an emphasis on team-based and coordinated care focused on primary and preventive care and undergirded by electronic health records and other information technology (IT) tools. The workforce is at the heart of the healthcare delivery system, and work redesigns inevitably have repercussions on the roles and necessary skills mix of healthcare staff. In a more team-based approach to care with a strong health IT infrastructure, pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers can use standardized, evidence-based guidelines of care to take on more routine responsibilities, such as screening, outreach, and health education. Doctors and other clinicians can then focus on diagnosis and treatment of patients with more complex conditions, responsibilities for which their specialized education makes them uniquely qualified. Accordingly, education and training programs for incumbent and future pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers (indeed, for all workers) need to be adapted to meet the changing practices of healthcare delivery, to ensure that every member of the healthcare team contributes to the fullest extent of his or her training and capabilities.

Healthcare providers should view pre-baccalaureate workers as resources. The following recommendations are designed to help healthcare providers meet the triple aim while improving the career opportunities of pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers: Expand research and evaluation on new roles with increased responsibility for pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers; rationalize the patchwork state-level scope-of-practice framework governing the services that members of healthcare occupations can provide; and strengthen regional partnerships of healthcare employers, educators, workforce boards, and other stakeholders to meet the specific healthcare employment needs of local and regional labor markets.

2

Metro Area Data

Sex

Race/Ethnicity

Due to suppressed data, bars may not total to 100%.

Poverty Status

Percentages are relative to the federal poverty level—$22,350 for a family of four in 2011. E.g. 100%-200%

implies living between one and two times the federal poverty level.

Nativity

Brookings is a non-profit institution and the charts above were created using Highsoft software under a non-commercial license, the terms of which can be found here. Please note that Highsoft software is not free for commercial use.

3

Introduction

Workers in healthcare occupations account for a large and growing share of the U.S. workforce, accounting for more than 12 million jobs, or about 9 percent of all workers in the U.S. economy. Between 2000 and 2009-11, the number of workers in healthcare occupations in the U.S. increased by 39 percent, or 3.4 million jobs.1 The Department of Labor projects that healthcare occupations will show strong growth between 2012 and 2022, adding nearly three million more jobs.2 Specifically, occupations in which substantial shares of workers have less than a bachelor’s degree are growing the most and the fastest. These include home health aides, nursing aides, personal care aides, licensed practical and vocational nurses, medical assistants, registered nurses, physical therapist assistants/aides, diagnostic medical sonographers, occupational therapy assistants/aides, and dental hygienists.3

The healthcare industry is experiencing dramatic challenges. It faces rapidly increasing demand from a surging older population plus vibrant bio-medical and technological innovation transforming care. At the same time it faces directives to expand access, reduce costs, redesign the financing and delivery of care, and most importantly, improve health outcomes.

In concert with other forces shaping the industry, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) has far-reaching implications for the healthcare workforce. While the ACA legislation is thousands of pages long and its implementation is an unfolding saga, its basic aims are fairly easily described: make healthcare accessible to more people, control healthcare costs, and improve the healthcare delivery system.4 There has been no shortage of critiques to date of health care’s fragmented delivery system, acute-care focus, volume-driven reimbursement methodology, and a professional scope of practice framework that inhibits flexibility and teamwork among staff. The ACA’s provisions on how providers are reimbursed and how medical care should be organized and delivered are intended to build on previous reforms and spur innovation to achieve the “triple aim” of improving the experience of health care, improving health, and reducing per capita costs.5

The ACA’s support of alternative payment and service delivery models through such means as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Innovation Center will alter the mix and responsibilities of healthcare staff among participating organizations.6 As these alternative models are tested and refined and demonstrate success, the goal is to scale them up and spread them throughout the healthcare system. For example, teams are central to Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs), both of which seek to reduce costs and improve care by increasing screening and preventive care and ensuring that care is better coordinated across providers. ACOs are groups of doctors, hospitals, and other healthcare providers who work together to provide coordinated care to specific sets of patient, often Medicare enrollees. PCMHs are primary care practices that build strong relationships between patients and physicians backed up by coordinated healthcare teams and electronic health systems. In both models, the specific team configurations are based upon the patient population and practice size and type, but a primary care team might include physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, registered nurses, social workers, dieticians, licensed practical nurses, medical assistants, or community health workers.7 Consequently, there is renewed attention to questions of how to educate and train the healthcare workforce (both new and incumbent, and at all levels of educational attainment) to work in service delivery models that emphasize team-based care and care coordination.8 In fact, the ACA created a National Healthcare Workforce Commission to analyze healthcare workforce issues and advise policymakers. Although Commission members were appointed by September 2010, it has never met nor conducted any business, since Congress has declined to fund it.9 Additionally, the National Governors Association recently announced that seven states will participate in a policy academy focused on the preparing the healthcare workforce for a changing health care environment.”10

The need to slow healthcare spending growth inevitably includes a review of healthcare staffing patterns, since more than half (57 percent) of healthcare expenditures are labor costs.11 Healthcare occupations span the education and earnings continuum, including workers with graduate degrees and years of specialized training and those with a high school diploma or less. While many discussions of the healthcare workforce focus on doctors and other professions with advanced degrees, workers with lower levels of education make up a large share of the healthcare workforce and carry out functions critical to an effective healthcare system. The training and skills of healthcare workers in supportive and assistive roles are central yet often overlooked in generating quality care and patient satisfaction.12 Alternative payment and delivery models, such as those supported by the CMS Innovation Center, open up possibilities for what we call “pre-baccalaureate” healthcare workers—those with less than a bachelor’s degree—to play enhanced roles in providing high-quality care in a more efficient manner and at lower cost. (Please see the Methodology section for more information on the specifics of how pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers and occupations are defined.) Pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers can take on more responsibility for screening, patient education, health coaching, and care navigation, and by doing so, free up doctors and other advanced practitioners to focus on the more complex medical issues for which they are uniquely qualified.

This analysis of the pre-baccalaureate healthcare workforce is designed for leaders in healthcare, education, and workforce development, particularly those working at the regional level. Understanding the size and characteristics of the pre-baccalaureate healthcare workforce is critical for regional leaders who want to deliver high-quality healthcare while adapting to new models, as well as for educational and workforce officials charged with preparing current and future workers for a changing workplace. Because healthcare offers large numbers of jobs for workers with less than a bachelor’s degree, these jobs are important for efforts to support upward social mobility, since they can serve as entry points into the labor force for workers with lower levels of education and potentially open up career ladders.

4

Methodology

Identifying and Selecting Pre-baccalaureate Healthcare Occupations for Analysis

To identify pre-baccalaureate healthcare occupations, we used the U.S. Department of Labor’s Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system, specifically the two major healthcare occupation groups: 29-000: Healthcare Practitioners and Technical Occupations and 31-0000: Healthcare Support Occupations. However, the analysis also includes one occupation not classified as healthcare. Personal care aides (SOC code 39-9021), within the major group 39-000: Personal Care and Service Occupations, are included based on their similar job duties as the healthcare occupations of nursing assistants and home health aides.13

To assess the educational levels of workers in healthcare occupations and develop the threshold criteria that would designate an occupation as “pre-baccalaureate,” the 2009-2011 American Community Survey (ACS) 3-year pooled microdata were used.14 We used the educational attainment of incumbent healthcare workers to define occupations as “pre-baccalaureate,” rather than the system classifying occupations by typical education required for entry developed by the U.S. Department of Labor, for several reasons. Using the educational level of current workers allows us to more directly measure employer preferences as shown by their hiring decisions, and also allows us to examine the range of educational credentials held by workers within a given occupation, since the typical education required for entry does not always preclude workers with other educational backgrounds from performing the same job.

Using the ACS, we examined the distribution of educational attainment (less than high school, high school diploma or equivalent, some college, associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, graduate or professional degree) among workers in healthcare occupations in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas. Shares of workers who were pre-baccalaureate—with educational attainment equaling an associate’s degree or less—ranged from 94 percent (licensed practical and vocational nurses) to 0 percent (dentists, among other occupations). Since there is no standardized definition of what share of the workforce of a given occupation should have less than a bachelor’s degree in order to be designed a “pre-baccalaureate” occupation, we examined the educational distribution to identify patterns and any natural breaks. The threshold of 37 percent of workers emerged as a natural break in the distribution: 37 percent of “all other healthcare practitioners and technical workers” hold an associate’s degree or less, followed by 30 percent of “recreational therapists”). We adopted 37 percent of workers holding an associate’s degree or below as our education threshold and classified these occupations as pre-baccalaureate. In other words, more than one-in-three workers in what we define as pre-baccalaureate healthcare occupations hold an associate’s degree or below.

Three-year pooled microdata from the 2009-2011 ACS was also used to provide data on the number, earnings and demographic characteristics of workers in pre-baccalaureate occupations at the metropolitan level. Unfortunately, occupational categories from the ACS do not always perfectly match most 6-digit SOC codes for detailed occupations, instead providing some occupations at the 6-digit detailed occupation level and the remaining at the 5-digit broad occupational level. Thus, the final list of pre-baccalaureate healthcare occupations includes both 6-digit detailed occupations and 5-digit broad occupations and there are some detailed occupations this report cannot analyze on their own.15 For example, ACS provides data on the 5-digit broad group of nursing aides, psychiatric aides, and home health aides, and does not allow analysis of nursing aides on their own, separate from psychiatric aides and home health aides.

Twenty-four occupations in the ACS meet the criteria that 37 percent of workers have an associate’s degree or less, as shown in Table 1.16 To streamline the analysis, the report focuses on the 10 largest pre-baccalaureate occupations, which account for the vast majority (85 percent) of all pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas.

Table 1. Healthcare Occupations with High Concentrations of Pre-baccalaureate Workers, Top 100 Metropolitan Areas, 2009-2011

| SOC Code | Occupation Title | Number of workers | Share Pre-BA | Number of Pre-BA workers | Rank by size of Pre-BA workers |

| 31-1010 | Nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides | 1,341,000 | 90% | 1,209,000 | 1 |

| 29-1141 | Registered nurses | 1,750,000 | 39% | 680,000 | 2 |

| 39-9021 | Personal care aides | 618,000 | 88% | 542,000 | 3 |

| 29-2061 | Licensed practical and licensed vocational nurses | 364,000 | 94% | 343,000 | 4 |

| 29-2050 | Health practitioner support technologists and technicians | 322,000 | 81% | 262,000 | 5 |

| 31-9092 | Medical assistants | 281,000 | 90% | 253,000 | 6 |

| 31-9091 | Dental assistants | 183,000 | 90% | 165,000 | 7 |

| 29-2030 | Diagnostic related technologists and technicians | 194,000 | 74% | 144,000 | 8 |

| 29-2010 | Clinical laboratory technologists and technicians | 231,000 | 45% | 101,000 | 9 |

| 29-2041 | Emergency medical technicians and paramedics | 104,000 | 83% | 86,000 | 10 |

| 31-909X | Healthcare support workers, all other, including medical equipment preparers | 97,000 | 88% | 85,000 | 11 |

| 31-9011 | Massage therapists | 98,000 | 75% | 74,000 | 12 |

| 29-2021 | Dental hygienists | 99,000 | 61% | 61,000 | 13 |

| 29-2090 | Micellaneous health technologists and technicians | 83,000 | 68% | 56,000 | 14 |

| 29-2071 | Medical records and health information technicians | 69,000 | 81% | 56,000 | 15 |

| 31-9097 | Phlebotomists | 59,000 | 88% | 52,000 | 16 |

| 29-1126 | Respiratory therapists | 64,000 | 67% | 43,000 | 17 |

| 31-9094 | Medical transcriptionists | 39,000 | 85% | 33,000 | 18 |

| 31-2020 | Physical therapist assistants and aides | 41,000 | 73% | 30,000 | 19 |

| 29-2081 | Opticians, dispensing | 33,000 | 82% | 27,000 | 20 |

| 31-9095 | Pharmacy aides | 29,000 | 80% | 23,000 | 21 |

| 29-9000 | Other healthcare practitioners and technical occupations | 53,000 | 37% | 20,000 | 22 |

| 31-2010 | Occupational therapy assistants and aides | 8,000 | 83% | 7,000 | 23 |

| 29-1124 | Radiation therapists | 8,000 | 54% | 5,000 | 24 |

Analyses are based on the 100 largest metropolitan areas in the United States, defined by population size in the 2010 decennial census. The metropolitan areas are based on the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) 2009 delineation of the 2003 standards, the delineation that corresponds to the 2009-2011 microdata used in the analysis. Geographies are standardized between years.

5

Findings

A. Workers with less than a bachelor’s degree in the 10 largest pre-baccalaureate healthcare occupations total 3.8 million, accounting for nearly half (49 percent) of the total healthcare workforce in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas.

The 3.8 million pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers in the 10 largest pre-baccalaureate healthcare occupations account for the vast majority (85 percent) of all pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas (see Figure 1). In other words, most pre-baccalaureate healthcare staff work in the 10 occupations that this paper will examine in detail. As described in the Methodology, these 10 are the largest healthcare occupations in which 37 percent or more of the workers have an associate’s degree or below. Occupations with the highest numbers of pre-baccalaureate workers include nursing, psychiatric and home health aides (1.2 million), registered nurses (680,000), personal care aides (542,000), and licensed practical nurses (343,000). Please see Appendix A for a description of the duties and responsibilities of each of the 10 highlighted occupations.

The Ten Largest Pre-BA Occupations As A Share Of All Healthcare Workers

In The Top 100 Metro Areas, 2009-2011

As with other economic activity, the healthcare workforce—at all educational levels—concentrates in metropolitan areas: The nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas are home to 7.8 million healthcare workers, accounting for 65 percent of the national healthcare workforce of 12.1 million. Nationally, pre-baccalaureate workers are also concentrated in the occupations highlighted in this paper, with the 6.3 million pre-baccalaureate workers in the 10 largest pre-baccalaureate healthcare occupations accounting for 85 percent of all pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers in the United States. Pre-baccalaureate healthcare workers make up a slightly higher share of all healthcare workers (61 percent) nationally compared to the top 100 metropolitan areas (57 percent), suggesting that the healthcare workforce is slightly more educated in metropolitan areas relative to the nation as a whole.

The total size of the workforce varies by occupation, as does the size of the pre-baccalaureate workforce, as shown in Table 2. Although a clear majority of workers in the 10 selected occupations have an associate’s degree or less (70 percent), some workers in these occupations do have bachelor’s degrees or above. Registered nurses have the largest total number of workers (1.7 million) and the second highest number of pre-baccalaureate workers (680,000).17 Nursing, psychiatric and home health aides have the highest number of pre-baccalaureate workers by far (1.2